On Wednesday, the UK newspaper The Guardian published a survey of IPCC contributors asking about their perspective on future temperature rise (Link). The survey received significant media attention and uptake in both the science and policy community. Theia Finance Labs, together with the Inevitable Policy Response, last year ran a similar survey asking climate policy experts and sustainability professionals as to their temperature expectations, as an input into the IPR forecasting process. Here, Theia Finance Labs Co-Founder and Director Jakob Thomä walks us through the 5 major problems with the Guardian survey in the latest Theia blog post.

- The community of scientists contributing to the IPCC report have a range of different research areas, from adaptation to mitigation, from economics to physics, and more. As outlined in a blogpost by Michael Liebreich, none of the experts interviewed for the article themselves are energy system experts for example (Link). They are all obviously ‘climate experts’ in some sense and have profound insights to bear on the challenge of preventing the climate crisis. But the question of what the future is likely to look like requires a particular expertise and analytical focus. It requires a) understanding the current policy landscape, b) an analytical perspective on what the policy landscape is set to look like in the future, coupled with market trends, and c) the ability to translate a) and b) into emissions pathways for land and energy, and ultimately temperature implications. Leading IPCC climate scientists themselves have also made this point. Michael Mann critiqued the survey on exactly this basis, as did other prominent voices like Katherine Hayhoe.

IMPLICATION: THE SURVEY SAMPLE MEANS THE RESULTS ARE NOT ‘A SAMPLE OF EXPERTS FORECASTING THE TRANSITION THINK X’.

- The question can be interpreted in many different ways. The Guardian article asked “How high above pre-industrial levels do you think average global temperature will rise between now and 2100?” The discussion of the article across social media shows that in fact this question can be interpreted in many different ways, likely making the results hard to compare. Scientists like Glen Peters have pointed out that most people likely interpreted this question as ‘what are we currently ‘on track’ for in terms of temperature rise’. In surveys run by IPR, both in interview and survey format, some people have understood the question in terms of when temperatures will ‘peak’, noting that a range of scenarios predicts that temperatures in 2100 are likely to be lower than their peak (e.g. IPR FPS). In a survey run by IPR, the average difference between ‘peak’ and ‘end point’ was ~0.1°C. One scientist surveyed by IPR forecast 1.2°C warming in 2100 given the expectation around the deployment of geoengineering. Other scientists remarked on other confounding factors (e.g. super volcano eruption) that would potentially impact overall temperature levels. Running surveys is hard and there is a whole discipline related to qualitative research methods. Here, a more science-based approach would likely have helped in the survey design and interpretation.

IMPLICATION: THE PHRASING OF THE QUESTION AND ITS DIFFERENT INTERPRETATION MEANS THAT TEMPERATURE QUESTIONS ARE NOT NECESSARILY A GOOD PROXY FOR EXPECTED CLIMATE AMBITION.

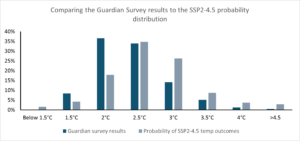

- The survey seems to simply replicate the distribution of the current-policy-type SSPE2-4.5 scenario. As outlined by Zeke Hausfather on Bluesky, the distribution of the survey results largely mirrors the probability distribution of the ‘current policy’ SSP2-4.5 result. 85% of respondents results were between 2-3°C, comparable to the 79% probability from the SSP2 scenarios. While on a granular level the survey is slightly more optimistic within the 2-3°C distribution band, some of this may also be the policy momentum between the last SSP2-4.5 analysis and the survey.

IMPLICATION: THE SURVEY LIKELY EFFECTIVELY REPRESENTED PEOPLE’S PERSPECTIVE ON WHAT HAPPENS UNDER CURRENT POLICY, WITH SOME ASSUMPTION AROUND ACCELERATION RELATIVE TO THE LATEST IPCC SSP2-4.5 SCENARIOS.

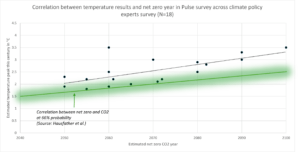

- There is strong evidence that even experts have the wrong temperature ‘priors’. Inevitable Policy Response ran a ‘pulse survey’ with climate policy experts and sustainability professionals in 2023 with a similar format to the survey run by the Guardian. In this survey, experts were asked as to their expectations around peak temperature, temperature in 2100 and net zero years for CO2 and GHG emissions. The results demonstrated little to no understanding among sustainability professionals as to the relationship between net zero years and temperatures, with effectively no correlation between the two. But even in our admittedly more limited climate policy expert sample of 18 respondents, there was a systematic misalignment between the net zero response and temperature response of around 0.3-0.5°C (see image below). Of course, the issue is not that straightforward, given the uncertainty around defining how temperatures will evolve given feedback loops etc and so this ‘bias’ may in fact just represent a higher degree of pessimism around climate forcing. This again highlights questions of risk. As outlined by Ilmi Granoff, the ‘bias’ may be a result of seeking to define ‘how bad it will get’, suggesting that even if temperatures are lower, impacts at lower temperatures are higher than people think (i.e. a 2°C world is as bad as people’s perception of how bad a 3°C world will get). Again, all this shows is how complicated such research is. But if we take current best available science as given, there is a clear bias in the temperature projections, suggesting that surveys of temperatures underestimate climate optimism.

IMPLICATION: THE SURVEY LIKELY HAS A BIAS IN TERMS OF THE ‘ACTUAL’ DECARBONIZATION PROJECTION.

- Current or implemented policies are not a forecast of the future. As outlined above, it seems the Guardian survey most likely captured a combination of a) People’s optimism / pessimism about climate forcing impacts of ‘current policy’, b) a slight upward adjustment of optimism since the last IPCC, while still c) underestimating their actual ‘optimism’ when considering views around net zero years. By that measure, ‘actual’ beliefs from this community based on our surveys, interviews, and public statements likely coalesce around ~1.8-2.2°C as an actual median response, although of course we are here in the territory of guesstimates based on a disparate set of information. In the IPR sample of climate policy experts (the kind of experts Michael Liebreich has identified), the average response for net zero CO2 was in the early 2060s, roughly consistent with the IPR forecast of keeping temperatures well-below 2°C. More broadly, there is often in the discourse a confusion around the extent to which ‘current policies’ represent a forecast. They do not. In this way, the criticism of organizations like the IEA is often misplaced as their ‘scenario’ on implemented or current policies (currently labelled STEPS) is not in fact a forecast. Indeed, one could just as well suggest that the IEA APS (Announced Pledges Scenario) should be treated as the ‘baseline’ as it represents actual policy pledges (and would be consistent with 1.8°C warming).

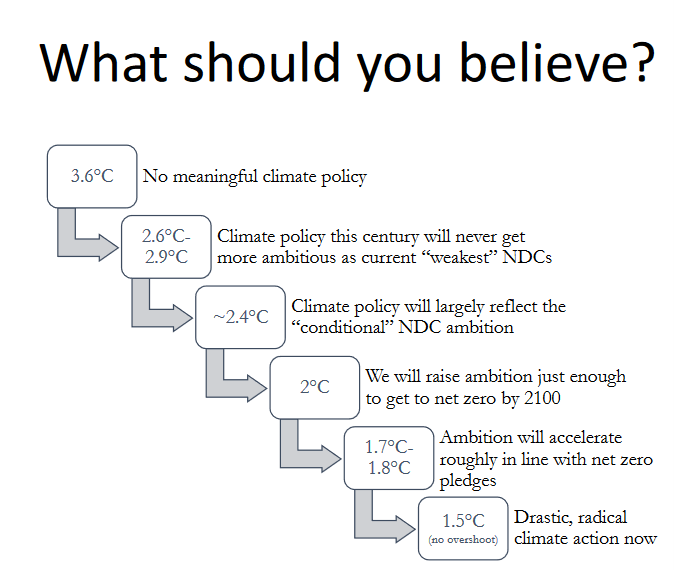

How should you think about the likely future?

The question then is what the future will actually look like? Will it represent a continuation of ‘current policies’ with basically no acceleration of current policy ambition (~2.4-2.9°C world according to most estimates). Such a future would imply current net zero year targets are not just breached but effectively abandoned entirely, with net zero moving back 40-60 years or perhaps even longer. This kind of policy pessimism flies in the face of significant and continuous global policy acceleration (from 3.6°C in 2015 to 2.4°C in 2023 according to the IEA), but of course is one way to think about the future. It is the implied assumption – taking the survey at face value – of the Guardian article (which as this article notes, is not advisable).

Alternatively, will we see the ‘policy forward-sliding’ / momentum / ratchet we saw over the past decade (Link) continue and the kind of future IPR forecasts become reality, with eventually an achievement of the ‘well below 2°C goal’ of the Paris Agreement (Link)? As IPR’s recent Policy Tracker shows, there is some evidence to that effect (Link).

Of course, there are other futures too, another reminder why temperature can ‘hide’ many different stories for this century. One could imagine a scenario where policymakers give up on decarbonizing and pivot to geoengineering in the face of the urgency of the climate crisis (e.g. if 1.5°C warming already becomes ‘unmnanageable’ politically in countries like India, it is unlikely that there would be patience for a 30-50 year decarbonization pathway, nor for a roadmap to 2.5°c or beyond). No net zero, but contained warming.

One could also imagine that certain climate impacts will not be as significant as the IPCC projects and that in fact the political ‘temperature equilibrium’ is higher (i.e. a 3°C world with 1.5°C impacts). For obvious reasons, this seems unfortunately a pipe dream.

Finally, there are those who believe climate will trigger a societal breakdown that ultimately creates a level of political instability that makes concerted political action impossible and so we may want to take climate action but no longer have the means to do so. However, at that stage, such breakdown would likely imply a collapse of economic activity in parallel that would also ultimately curb emissions dramatically.

The Guardian article, despite its flaws, shows that people are asking these questions and want answers. IPR is launching a first of its kind ‘transition forecast workshops’ this year allowing financial institutions to participate in the forecasting process and develop answers that make sense for them, surface ‘actual’ market and expert sentiment around the nature of the transition not at temperature level but on the ground net zero dynamics, support engagement, and can inform mandate design and capital allocation. If you are interested, reach out to find out more how you can participate in these workshops. Email me at jakob@theiafinance.org

Note: This blog post was written in response to the Guardian article and forms part of Theia Finance Labs blog series. It is written in personal capacity and publication under the Theia brand does not imply endorsement by the Theia ventures (e.g. 1in1000, tilt) or the Inevitable Policy Response consortium. The author is responsible for all errors and omissions.