A lot of commentators are focused on what is happening in markets today. While it is tempting to trade on the volatility, long-term investors should ask themselves a more fundamental question: What will emerge from the chaos?

To understand what the world will look like in two, or five or ten years, we need to first understand the source of the imbalance that is driving the current chaos.

And no, it is not the current account deficit.

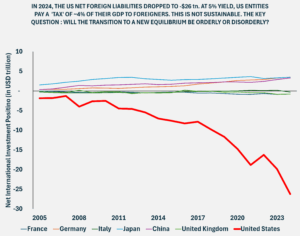

While Bluesky and LinkedIn posters have mocked the rudimentary confusion inherent to Trump’s approach to trade, there is another side of the trade ledger that has created a historically unprecedented imbalance in an obscure but crucial macroeconomic indicator: The Net International Investment Position (NIIP).

Over the past 20 years, foreign entities have built up a net stake in the US economy of $26 trillion, equivalent to almost 100% of US GDP (~$78,000 per capita), and equal to around 20% of US net wealth. In other words, the US owes the world $26 trillion more than the world owes the US.

Assuming the average yield on these assets is 5%, foreign entities have an effective claim on US economic activity of around 4-4.5%.

It may be funny to mock your trade imbalance with the supermarket. But at some point you have to still make money.

To put that number into context, the annual ‘economic extraction’ of France from its colonies during the Colonial Era is estimated by one study at 2% of GDP.

While the US administration policy actions are chaotic, they respond to a fundamental truth: The current situation is unsustainable

What Phoenix will emerge from the ashes…?

Over the next 5-10 years, the United States will have to dramatically devalue its liabilities. This will involve a three-pronged approach: currency devaluation, financial repression, and rebalancing trade.

Currency devaluation is already under way. The EUR-USD exchange rate dropped from 96 cents to 86 cents at time of writing within the span of 2 months. It does not seem unreasonable to conclude that the USD will settle at a new long-run equilibrium of 70 to 80 cents to the Euro, with similar movements against other major currencies like the Yen and Reminbi (the Pound may prove to be a sui generis given the idiosyncratic position of the UK economy).

A currency in freefall will drive up yields for foreign investors, a major buyer of US debt instruments. Higher yields however offset the benefits of reducing the value of international liabilities by increasing their return.

So the US will face a Catch-22 at this point. The Mar-A-Lago Accord envisions strongarming creditors into buying long-term low or zero interest instruments to resolve this issue. This seems implausible as a strategy, but crazier things have happened.

Failing that strategy, the US will be forced into using a combination of the Federal Reserve balance sheets and capital controls.

A massive quantitative easing program can suppress yields, but will obviously drive up inflation, which will in turn also drive up yields (and create an obvious tension for the Federal Reserve).

The long-term equilibrium here however is clear: Higher baseline inflation targeting of 4-5% (while this may seem politically toxic, inflation was higher than 3% from 1967 to 1986, a period of 20 years), lower currency value of 15-25% (dare I say 30%?) relative to the first two decades of this century, and (implicit or explicit) capital controls limiting domestic capital outflows that limit the increase in real yields (<100 basis points)

This would both dramatically reduce the US trade deficit and the net foreign liabilities. Reducing these liabilities in nominal terms by 20-30%, real yields increasing by 50 basis points (despite financial repression, it is unlikely that real yields would also not increase), and nominal GDP increasing by 30%-40% by 2030 could roughly halve the foreign tax to <2.5% of GDP. At this point, there is a long-run pathway established that would likely further reduce that number to <2% in the 2030s.

This still leaves a number of open questions. What happens to global GDP? What happens to other markets and asset classes?

There are some obvious effects.

I predict we will see some of the first global effects in commodity markets, which will achieve a new equilibrium as they move inversely to USD values, settling at higher rates despite economic instability. Of course, this will be a nominal effect in the first instance. Oil will not in fact become more expensive for Europeans. Real energy prices are likely to remain repressed in an uncertain, low-growth environment.

There will be obvious exceptions. Some commodities will become more expensive due to supply chain effects. And fundamentals (e.g. agricultural commodities, clean energy minerals and metals) as well as ‘safe haven’ considerations (e.g. gold) will do their part.

Second, we will see the rise of ‘safe havens of last resort’. In the first instance this will be other major markets (Europe, Japan, Switzerland, and yes, China).

As safe havens of last resort prove (at least in their current configuration) unable to stem the role the US Treasuries played, we will see negotiations as to the development of new reserve currencies to price contracts in international trade. and build size and liquidity This could be imagined as the IMF Special Drawing Rights 2.0 or a more bottom-up collaboration and even a new era of currency consolidation (as crazy as that sounds).

Third, I am overall optimistic about economic growth in the medium-term. These market frictions will obviously inhibit economic growth. At the same time, they may drive more medium-term stability. A low-interest rate environment will offset some of the risk premia spikes that come with political instability. Productivity gains can be expected from the clean transition by driving global electrification, a long-run decline in both energy prices and energy price volatility, and a ‘de-commodification’ of energy.

Ultimately, I think global markets will replace the US demand loss and that productivity fundamentals will support a more broad-based economic development.

It may at this point sound insane but there is plenty of economic development left. China’s GDP per capita is still lower than Montenegro’s (and the world average).

There may even be a ‘Brexit effect’ with a political reset of the popularity of populist parties.

This language may set off alarm bells for the degrowth movement. I am not interested in debating this here. Simply put, there is a future where people can live in prosperity without the US running a $1 trillion current account deficit. Dare to imagine it!

Of course, there are major downside risks to growth driven by political instability and the social tipping points from climate impacts (e.g. migration, conflict for resources, spiking risk premia, spiking real depreciation rates, economic dislocation). But these should be distinguished from the fundamental repositioning of global markets currently under way, which do not have to be net negative.

Will the Phoenix be green?

I have been following the climate sceptic / denial community closely since the birth of my second son two and a half years ago (listening to climate denial podcasts were the only thing that would let me go back to bed after a 3 am bottle feed).

They have never been this exuberant.

I think we will look back on Trump as a Trojan horse (and I just don’t mean the emissions impact, that we estimate at 0.5 GT of CO2 annually from lower economic growth).

As Trump isolates the United States internationally, he also will isolate the anti-climate coalition.

Fossil fuel importers like Japan, Europe, and China will now face not just the OPEC power play, but also the fossil fuel power play of the United States. Energy independence will become more important than ever. And there is only one source that delivers it: clean energy.

The chaos of the Trump administration hides key truths. One is the macroeconomic imbalance. The other that we are indeed in a battle of ideas.

A man is judged by the company he keeps and a company is judged by the men it keeps. And the anti-climate movement keeps bad company.

This strategic weakness in the battle of ideas meets a moment where – at least for some industries and technologies – we are finally approaching the moment where “what’s good for business is good for the planet”.

I was about as pessimistic as I could have been in December 2024 when it comes to climate. I have not been this optimistic in years.

There is one important caveat: The end of net zero

We will pull our hair out over the coal fired power plants that will still be built and the US climate policy rollback.

But the real drama is in the R&D the Inflation Reduction Act was supposed to deliver to breakthrough technologies.

I simply cannot map the political economy that will deliver breakthrough technologies in the last hard to abate sectors (aviation, parts of industry, and the last 10% decarbonization of the power grid while maintaining grid stability) without the US operating as anchor funder.

I already struggled to map the political economy of countries agreeing to continue climate investment once warming slows to 0.1-0.2°C every 50 years (the likely speed of warming once we hit 90% emissions reduction). But without breakthrough technologies developed through core funding by US science, the chances seem all but zero.

The good news is that achieving that level of decarbonization (80-90% relative to current levels) over the next 30-50 years right now still seems like a fantasy to most people. For me, this is now a base case.

I would bet Dollars on it. Not sure how much they’d still be worth though…